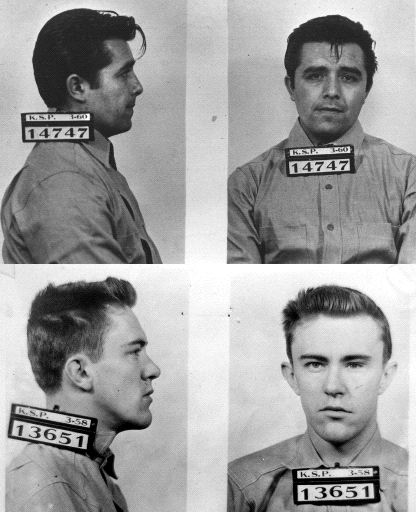

Truman Capote’s seminal true crime book In Cold Blood follows two dangerous ex-cons as they clumsily evade the police after brutally murdering a virtuous, god fearing Kansas farming family. It is a succinct, balanced portrayal of two deranged minds fueling each other’s worst impulses. When released in 1966, the book was wildly successful and a big screen adaptation was inevitable, so inherently filmable was the subject matter.

The story goes like this: Richard ‘Dick’ Hickock learns in prison of a wealthy Kansas farmer, Herbert Clutter, from his cellmate who used to work on Clutter’s farm. It is speculated that there might be a safe kept at the house containing at least ten thousand dollars. This speculation is based purely on the assumption that farmers USUALLY have a safe that PROBABLY contains thousands of dollars. Upon Hickock’s release he decides, along with fellow ex-con Perry Smith, to drive to the farm, steal the money and leave no witnesses alive. Just about as premeditated as murder can get. When they get to the farm to carry out their horrible crime they find that there is no safe and there is little more than forty dollars in total to be taken. Clutter’s ailing wife and sixteen year old daughter are tied up and shot to death in their beds with a shotgun. Clutter and his son are taken down to the basement where Clutter’s throat is cut before both he and the son are shot as well. A whole family ended for forty dollars and a transistor radio.

While Capote isn’t overly editorial in his writing, he writes about the plight of the Clutters with a great deal of compassion. Of course, it isn’t hard to have compassion for a family who is brutally murdered on the basis that they might have money hidden somewhere. What is striking is the compassion with which he writes about the killers, specifically Smith, with whom Capote formed an oddly special and complicated bond during the course of interviewing him for the book. Most of Smith’s relationships with men seem to be complicated – more on that later.

I was quite interested to see if this compassion would translate over into Richard Brooks’ 1967 film adaptation of the book. I was both delighted and disturbed to see that it had, and in a shockingly profound way. I was delighted because it is always a moving experience when a filmmaker and cast so understand the text that they can recreate, without manipulation, the spirit of it. I was disturbed because much of this was achieved by the sensitive, nuanced portrayal of Perry Smith by Robert Blake. Now, some may say it should be no big stretch for Blake to portray a cold, calculated murderer, as he proved it to be his nature when he murdered his own wife years later (yeah, I have less of a problem editorializing than Truman Capote). But his performance in this movie was far more convincing and complex than his performance in a real life court of law (though he was apparently just convincing enough to be acquitted).

The nature of Smith’s relationship with Hickock is handled with the most amazing subtlety. does Hickock call Smith ‘honey’ and ‘baby’ in the colloquial parlance of 50’s popular culture, or were these pet names denoting an undercurrent of sexual familiarity? Draw your own conclusion. Either way, their roles are clear: Hickock is the smooth, confident alpha with his finger on the button and Smith is the unstable atomic bomb just waiting to be deployed.

There is a scene early on in the manhunt where the detective investigating the case, detective Alvin Dewey Jr. (John Forsythe), visits Smith’s father. He tells Dewey the story of how he raised Perry on his own after heroically wresting him from the guardianship of his alcoholic, cheating mother. Throughout the rest of the film Smith’s father appears to him in hallucinations, filling out the back story of their relationship and deftly illustrating how Perry Smith became a confused and vengeful murderer. The film doesn’t set out to alleviate the killers of responsibility, but rather to show that evil and misguided aggression are not necessarily inherent, but perhaps precipitated by the events of our formative years. And that is a powerful message.

The film is tied together by one of the most satisfying scores I’ve ever heard, courtesy of Quincy Jones. The through line of the score is built on the low, menacing upright bass sound, over top of which is sat everything from cool, laidback trumpet and rolling snare hits to urgent, clamoring percussion that forces a sense of impending danger and hysteria. There are sweeter moments; the theme that underscores the pre-murder scenes of the Clutter family is extremely serene and wholesome, but the majority of the score is at once super-cool and unsettling.

There is no reason not to see this movie – okay, maybe in protest of Robert Blake being a terrible monster in real life. But I would wager you know just as well as I do that celebrity monsters are all eventually exonerated by time and excellent work (Roman Polanski, Ike Turner, probably Mel Gibson sooner or later) so I suppose if you can set aside judgement of the man himself you will be rewarded.

No judgement if you can’t though, I mean, the guy is a fucking murderer.

Casey Lyons

October 9, 2013

No Comments

By admin